Izak Odendaal, Investment Strategist at Old Mutual Wealth

After a brief hiatus, US President Donald Trump’s trade war is back in full swing. Or is it? The 90-day suspension of the reciprocal tariffs announced in April has now expired, and Trump sent letters to countries outlining where they stand. For the most part, the tariffs are very similar to those proclaimed on what Trump termed “Liberation Day”, April 2. The only difference seems to be rounding, so that South Africa gets 30% instead of 34%, as was the case in April. Have we gone full circle?

Not quite. The tariffs are set to take effect on 1 August, leaving some room for negotiations. However, trade deals normally take years to finalise and are incredibly detailed. So far, only Vietnam, Indonesia, China and the UK have managed to reach an agreement with the US, and these have been fairly vague. Uncertainty persists.

Taco

In contrast to the market sell-off after the first Liberation Day, the response this time round has been very muted even though the proposed tariff levels are very similar. The S&P 500 continues to trade near record highs, and the strength of the market, along with ongoing resilience in the US economy and the recent passage of the Big Beautiful Bill, has probably emboldened Trump to get tough on trade again. The tariffs have also already raised quite a bit of revenue for the government – $50 billion in May and June – without severe economic consequences so far.

Chart 1: S&P 500 index

Source: LSEG Datastream

This is consistent with a pattern stretching back to Trump’s first term, namely going on the attack when the wind is in his sails and pulling back when there are headwinds. This is exactly what happened in April, when the market crash caused him to suspend most of the tariffs. For this reason, the idea of TACO -Trump Always Chickens Out – has taken hold with investors. The market now fully believes that this is a bluff and a negotiation tactic, and that the final tariffs will not be as high as currently threatened.

The problem is that something or someone will need to convince Trump to back down and accept more reasonable tariffs. The someone could be Republican politicians, worried about a voter backlash, or the CEOs of major companies, concerned about their margins. The something would be an adverse market reaction or bad economic data. Neither is likely until there is some unhappiness.

Even then, Trump is clearly committed to the idea of higher tariffs. There is no doubt that tariffs will settle well above the 3% level they averaged at the start of the year. Where and when they settle remains an open question. An average tariff rate of 10% to 15% is very high, but manageable and can probably be absorbed by various players across the value chain without significant damage. More than that, and someone, probably the end consumer, faces a price shock.

For now, there is economic resilience. America’s biggest banks reported second quarter earnings last week, and they all noted that their customers were not showing major signs of stress. However, this doesn’t mean it is a rosy picture. Companies stockpiled goods before the tariffs kicked in meaning that consumers have not been exposed to the full extent of price increases yet. And while labour market data does not point to mass layoffs, people who have lost jobs are struggling to find employment. A further drag is the mass arrests of undocumented immigrants and sharply lower numbers of new immigrants. This has probably not showed up in official employment data yet, but nonetheless implies fewer people available to work and therefore earn and spend.

All this still points to a softening of the US economy towards the end of the year, something that was likely to happen anyway, but that new policies will intensify. Ultimately the tariffs have to show up as some combination of higher consumer prices, lower sales (where people refuse to pay more) and squeezed corporate margins (when firms cannot pass tariff costs on). Exporters will bear some of the pain, but most of it will fall on Americans.

Toasters

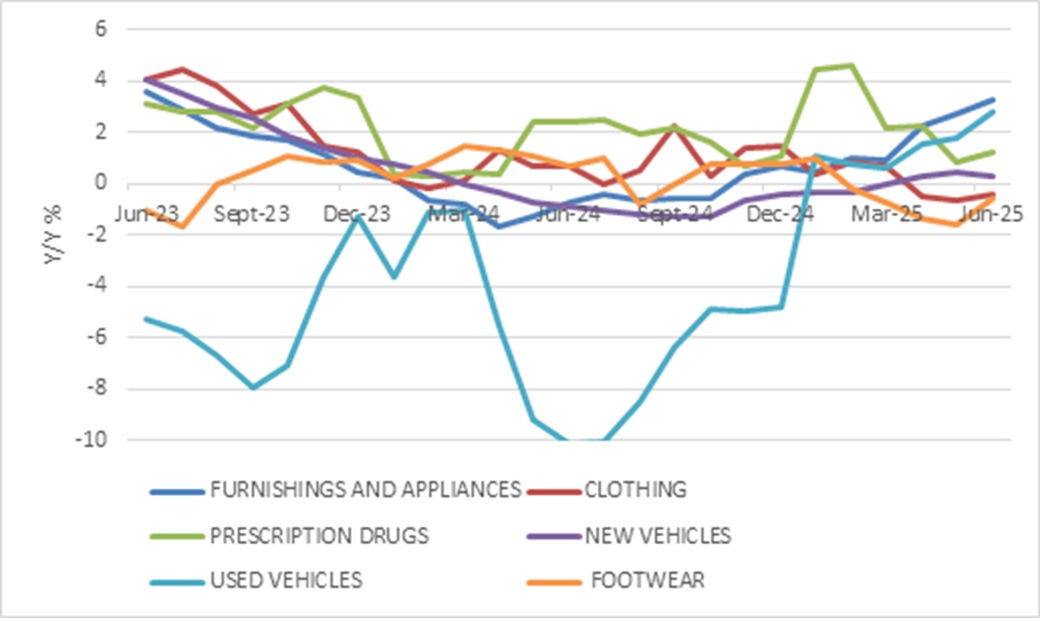

There are already hints of rising consumer prices for goods. Remember that services account for two-thirds of the US consumer price index (CPI), and of that, a substantial portion is related to housing rents, which continue to fall gradually from elevated levels.

The June CPI shows that prices are rising for appliances, such as toasters and microwaves, and also clothing. These are goods that are predominantly imported.

Chart 2: US goods price inflation

Source: LSEG Datastream

Tariffs will cause once-off price increases, but not necessarily sustained inflation. For one thing, tariffed goods are only a portion of the CPI, as noted, and more importantly, in an environment where the economy is cooling, businesses’ pricing power is eroded.

It does muddy the water, however, by causing short-term upward pressure on inflation gauges. Against this backdrop, the Federal Reserve remains reluctant to cut rates. It doesn’t want to repeat the mistake of 2022 when it thought that the supply chain distortions would result in only “transitory” inflation. It will likely remain on pause at the end-July meeting, but the next meeting in September could see it resuming rate cuts. Unfortunately for the Fed, its decision-making is now further complicated by outside forces.

Fire

Trump continues to demand that the Fed cut rates sharply. He has amped up personal attacks on Fed Chair Jerome Powell, whose term in office ends in May, and has openly mused about firing him. The president probably does not have the legal authority to fire Powell, but a scandal is being concocted over cost overruns in renovating the Fed’s headquarters in Washington to potentially force him out. Either way, Trump will get to choose Powell’s replacement and has already made it clear he will choose someone to do his bidding.

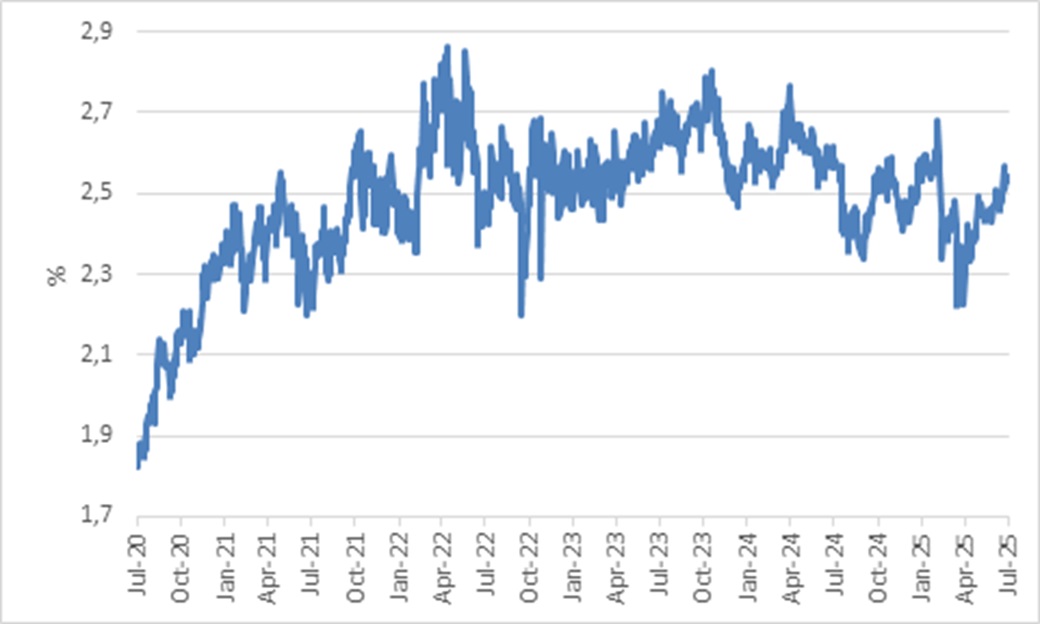

Central bank independence is a relatively new concept in economics, but one that is now widely considered to be crucial. Central bankers should be able to set interest rates with the long-term interests of the country in mind and not be beholden to politicians or the electoral cycle. In particular, central bankers want the general public to believe that stable inflation will persist, anchoring their expectations of future inflation. The credibility of the central bank is key for maintaining this kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Firing Powell will not necessarily be enough to end the Fed’s independence, since the Federal Reserve System consists of a board of governors and 12 autonomous regional banks. Nonetheless, the Chair has considerable influence over monetary policy, and this is and should be a big worry for investors. Market expectations of future inflation have already started increasing again, though not to worrying levels yet (Chart 3), and Powell-bashing has weighed on the dollar.

Worst of all, it will be counterproductive. Trump wants lower rates to reduce the government’s borrowing costs. However, while the Fed controls the overnight fed funds rate, longer-term borrowing costs (bond yields) are determined by the market. Rising inflation expectations would push these up. The US government could end up paying even more to borrow if Powell is replaced by a lacky. The only way to counter this would be to tilt new borrowing towards shorter maturities, but this comes with its own set of risks, namely constantly having to roll over maturing debt.

Türkiye (Turkey) is often cited as the poster child of eroded central bank independence. It’s had seven central bank heads in the past decade, many of them forced out by President Erdogan for not keeping interest rates sufficiently low for his liking. The result is a 90% depreciation in the lira against the dollar over this period, and a 28% average annual inflation rate. The US is not going to end up in such an extreme situation, but even the slightest move in that direction would be negative for US fixed income assets and the dollar. Fortunately, South Africa has an independent central bank, determined to go the opposite way: it wants to lower its inflation target to 3%, and cement inflation expectations there.

Chart 3: 5-year, 5-year Forward Inflation Swaps

Source: LSEG Datastream

The Fed is also one of the last truly non-political institutions in the US, with courts no longer qualifying for that label. Fed officials appointed by a president of one party have routinely been kept on by presidents from the other side. Powell was appointed by Trump, for instance, but his term was renewed by President Biden. Trump’s tariffs might not last past the end of his term, but the politicisation of the Federal Reserve could be a long-term legacy. Given the upheaval across US institutions over the past half-year, perhaps it is naïve to think that the Fed, headquartered only four blocks from the White House, can escape unscathed.

Oranges

From a South African point of the view, the 30% tariffs are a blow, though it is not necessarily the final number. The South African government has confirmed it is still talking to the US in search of concessions. The US is a big export destination for South Africa, but only around 8% of exports by value are destined for the American market. Of this, minerals and metals make up a substantial portion and are likely not impacted by new duties. In other words, the tariffs are not a recession-inducing threat for a local economy that benefits from more stable electricity supply, lower inflation and lower interest rates.

Nonetheless, some firms and sectors face major headwinds. One is agriculture, where citrus farmers in particular have built strong export links with the US. Since South Africa is in a different growing season to the US, its farmers don’t compete with American producers. This reiterates how shortsighted Trump’s approach to tariffs tends to be. Instead, South African orange farmers compete with other southern hemisphere growers, notably Chile and Peru. For the time being, they face a 10% tariff, giving them an advantage. Either way, American consumers are likely to pay more for oranges.

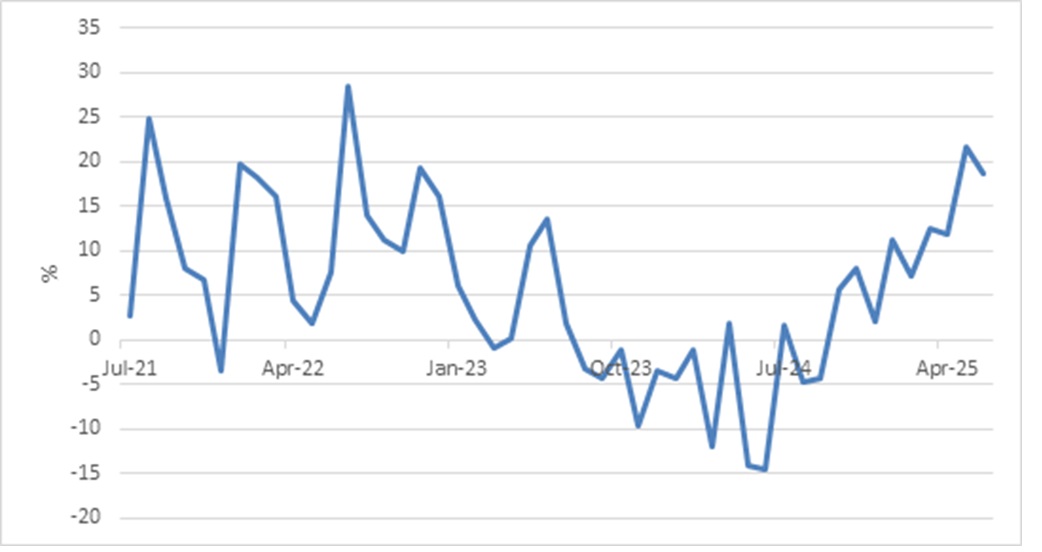

The other sector that is heavily impacted is the automotive industry. Exports to the US have already fallen sharply, and this might lead to parent companies scaling back local operations. This happens at the same time as competition in the domestic market is hotting up against Chinese imports, while the inevitable longer-term shift to electric vehicles poses another set of questions.

For now, however, growth in the new car market has picked up nicely after a rough patch, another sign that the local economy is doing better. Another interest rate hike is likely later this month, given a stable exchange rate and low reported inflation. This will further support the automotive industry.

Chart 4: South African Domestic New Vehicle Sales, year-on-year %

Source: Naamsa

Oversteering and understeering

Speaking of cars, drivers faced with a tricky situation often instinctively overreact, yanking the steering wheel this way or that. It is understandable but can make things much worse. At the same time, not reacting can mean smashing into something head-on. Similarly, investors need to be careful not to overreact to market volatility or scary news headlines. However, they also shouldn’t be complacent. The world is a particularly uncertain place, since US economic policy is unusually volatile. No-one really knows for sure how this plays out in the short term. In the long term, we know that fundamentals trump (no pun intended) sentiment and that companies will adapt to wherever tariff levels settle and get on with life. We also know that over the long-term, valuation is a strong guide to return expectations, and there are enough attractively priced asset classes available such that a diversified portfolio can deliver positive real returns for South African investors in the years ahead. It is likely to be a bumpy road, however.

ENDS